HOW I LEARNED TO IMAGINE AND TEACH THE COMMON GROUND

ALTHOUGH THEIR PROJECTS TAKE THEM TO PLACES AS DIVERSE AS COLOMBIA, PALESTINE AND THE BRAZILIAN RAINFOREST, ARE THERE LESSONS FOR US IN FACING CONFLICT IN DAILY LIVES?

IMAGINING COMMON GROUND

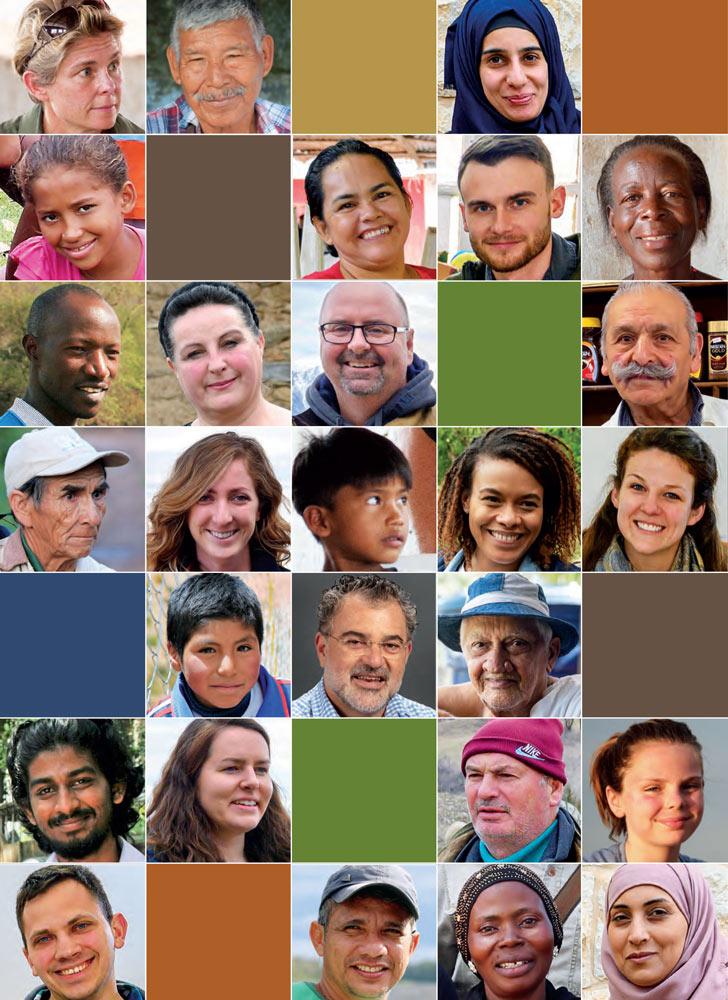

The images accompanying this story represent locations and projects during the 12-year history of Business on the Frontlines serving 56 projects in nearly 30 countries. Together, they tell a story of diverse people in far-flung locations, all seeking peace and dignity through economic stability. (Photos by Barbara Johnston, John Dunbar, Joe Sweeney (MBA ’12, ND ’06)

“Useless child.”

“Useless child.”

In Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries, there is no term to describe children who are physically or mentally disabled. And there are so many of them. As a result of unexploded ordnance left over from the war and the widespread use of Agent Orange, Vietnam has some of the highest disability rates in the world.

Historically, Vietnamese society has called people with mental or physical disabilities “useless,” “the lost ones” or “non-productive” because they are unable to care for their elders as children are expected to. Families often are embarrassed about them, hiding them away. There are very few opportunities for them to be educated, trained or developed.

I traveled to Vietnam in 2016 as a board member of Catholic Relief Services (CRS) to visit a highly successful program to build schools and training programs for these lost ones. At the time, the legacy of the Vietnam War was still very present. People named their children “Lenin” and “Marx” and their dogs “Nixon” and “Kissinger.”

And yet this amazing school came about through an unlikely tripartite partnership: the communist government of Vietnam; Catholic Relief Services, the international humanitarian organization supported by the Catholic community in the U.S.; and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), an independent agency of the United States federal government.

Consider: This is the same communist government that still persecutes people of the Catholic faith in Vietnam. That has closed Catholic churches and seminaries and has taken away the Church’s assets. Now, think about the government of Vietnam taking money from its former enemy, the United States, in the form of funding from USAID. And think about them partnering with Catholic Relief Services, which has the psychologists, the social workers, the teachers and the experience needed to create innovative programs to serve the disabled.

This was a partnership of three organizations that embraced such divergent ideologies and whose histories were fraught with conflict. They will not agree on faith. They will not agree on communism. They will not agree on foreign policy. It would have been easier and more socially acceptable for all three organizations to perpetuate their historic and ideological conflicts.

This was a partnership of three organizations that embraced such divergent ideologies and whose histories were fraught with conflict. They will not agree on faith. They will not agree on communism. They will not agree on foreign policy. It would have been easier and more socially acceptable for all three organizations to perpetuate their historic and ideological conflicts.

Yet the leaders from these three different organizations overcame their differences to imagine common ground amongst themselves. In this one circumscribed area with a picket fence around it — the betterment of the lives of the physically and mentally disabled — their leaders are civil to each other and work together toward a common goal. With commitment, even adversaries can imagine the common ground and then work to create it, to serve those who are more vulnerable than ourselves.

Before my work with Catholic Relief Services and the Business on the Frontlines program at the University of Notre Dame, I believed that the common ground was something that people already shared and then explored together. However, what I have learned in this last decade of work is rather the opposite: Common ground does not exist until we imagine it. And then we need to work ridiculously hard to create it.

ON THE FRONTLINES

The heart of what students learn in the Business on the Frontlines program is to imagine and then create common ground with others, often in regions and countries where violent conflict and deep poverty are a daily reality. To date, since the program was founded in 2008, nearly 60 teams of students and advisers have served in more than 30 countries. They have worked on projects ranging from the reincorporation of former combatants in Colombia to establishing supply chains around the world for coffee, cacao, grains, textiles, even fish from deep in the Amazon, to fighting the tragedy of human trafficking in Mindanao in the Philippines and Romania.

The heart of what students learn in the Business on the Frontlines program is to imagine and then create common ground with others, often in regions and countries where violent conflict and deep poverty are a daily reality. To date, since the program was founded in 2008, nearly 60 teams of students and advisers have served in more than 30 countries. They have worked on projects ranging from the reincorporation of former combatants in Colombia to establishing supply chains around the world for coffee, cacao, grains, textiles, even fish from deep in the Amazon, to fighting the tragedy of human trafficking in Mindanao in the Philippines and Romania.

The students walk into class with varying degrees of experience in working on deeply entrenched economic and societal issues. Some have served in the military, some have volunteered for local aid agencies. Many have no experience at all.

So we start at the beginning, with a reminder of what our goals are — as members of the Notre Dame community and as people concerned about the millions living in poverty and strife. As Father Ted Hesburgh, C.S.C., said, “We teach human dignity best by serving it where it is most disregarded, in the poor and abandoned.” Father Ted’s words continually remind us that we should never underestimate the human dignity associated with a good day’s work, particularly for those who have come through conflict and deep poverty.

We also remind students of the words of Pope John Paul II, “Be not afraid.”

The question then becomes how to prepare incredibly committed graduate students to travel thousands of miles to unfamiliar and sometimes difficult terrain to tackle societal problems that have existed for decades if not longer. In other words, how to prepare them to imagine possible common ground with people whose life experiences, backgrounds and perspectives are vastly different than their own.

Like anything worthwhile, it takes work.

NECESSARY ALLIANCES

Business on the Frontlines rests on the rather novel combination of four teaching approaches. First, we deliberately select partners who are doing good work in areas where we can send students to serve far outside their comfort zones. Second, we prepare students for respectful conversations with those whose perspectives differ vastly from their own. Third, we engage students on problems that business cannot solve on its own, necessitating alliances with other organizations that share common goals. And fourth, we assist them in a process of reflection on what they now believe given these new experiences once they return home.

Business on the Frontlines rests on the rather novel combination of four teaching approaches. First, we deliberately select partners who are doing good work in areas where we can send students to serve far outside their comfort zones. Second, we prepare students for respectful conversations with those whose perspectives differ vastly from their own. Third, we engage students on problems that business cannot solve on its own, necessitating alliances with other organizations that share common goals. And fourth, we assist them in a process of reflection on what they now believe given these new experiences once they return home.

In recent years, experiential learning has become a mainstay in business schools, and rightly so. Students learn valuable lessons by working on a project firsthand with a U.S. or global partner that serves a strategic and operational imperative.

It is one thing, however, to travel to India to work with an IT outsourcer on its expansion strategy. It is an entirely different challenge to travel to Honduras, as one of our teams did this year, and work with a community of illiterate peasants to build business opportunities in handicrafts, services and agriculture so that they could create better lives for their families.

In Business on the Frontlines, we begin with selecting our partners for their dedication to serving those most in need. Although our partners range from international humanitarian organizations to multinational corporations to governmental agencies, what they all share is an open-mindedness and willingness to change. Our projects then harness the students’ business problem-solving capabilities toward serving those chronically underserved populations facing tough problems in tough geographies.

Students collaborate with partners, while learning from their partners’ vast experiences and expertise. Across the entire spring semester, the teams engage in weekly calls with their partners on their projects for seven weeks and then travel to work alongside them for two dedicated weeks. Upon their return, the students again engage in weekly conversations with the partner organizations for another seven weeks, ultimately presenting proposed solutions to the problems posed by partners.

Our projects deliberately place our students in a context vastly different than their own. Indeed, our students will serve those in need in their homes and their comfort zones, while being far away from and far outside the students’ own. As a consequence, their work in the field challenges the students mentally, physically, emotionally, spiritually. The experience makes the complexity of these problems very real to the students. The motivation to work toward impacting their lives becomes pressing. Serving the most vulnerable sheds light on the human side of business.

Our projects deliberately place our students in a context vastly different than their own. Indeed, our students will serve those in need in their homes and their comfort zones, while being far away from and far outside the students’ own. As a consequence, their work in the field challenges the students mentally, physically, emotionally, spiritually. The experience makes the complexity of these problems very real to the students. The motivation to work toward impacting their lives becomes pressing. Serving the most vulnerable sheds light on the human side of business.

Second, our students must be able to handle challenging conversations in meaningful and respectful ways. During their service alongside partners in the field, the students and advisers confront exploitation, discrimination, repression, deep poverty and the legacy of armed conflict. Once again, preparation is critical.

The students thoroughly discuss diverse readings in class prior to traveling to serve in-country. The readings are expressly designed to challenge students in multiple disciplines beyond business, including economics, philosophy and politics. They range from Pope Leo’s encyclical “Rerum Novarum” to Ryszard Kapuscinski’s “The Other.”

Our guidance is that if a student begins to have a meaningful conversation in the field, but that conversation strays away from the project problem solving, then the project is put on hold. Instead, the student just listens. The conversation will be a gift in itself. The project will work out.

Third, as teams work toward making recommendations for the problem posed by our partners, students begin to realize that most challenges in society will not be solved by business alone. Working toward true impact in the lives of those they serve not only motivates the students, but also forces them to search out other allies who may also contribute to the overall solution. To illustrate, one of this year’s teams traveled to rural Colombia to work with PASO Colombia, a local NGO that serves FARC ex-combatants and coca-growing peasants. (Coca is the crop that is turned into cocaine.)

Third, as teams work toward making recommendations for the problem posed by our partners, students begin to realize that most challenges in society will not be solved by business alone. Working toward true impact in the lives of those they serve not only motivates the students, but also forces them to search out other allies who may also contribute to the overall solution. To illustrate, one of this year’s teams traveled to rural Colombia to work with PASO Colombia, a local NGO that serves FARC ex-combatants and coca-growing peasants. (Coca is the crop that is turned into cocaine.)

In 2016, the government of Colombia and the FARC signed landmark peace accords to end their 54-year civil war. Sadly, neither government nor private efforts have reduced the scourge of coca cultivation, which has spiked since the peace accords. This has led to high rates of violence and extortion in these areas, with entire pockets of the country outside of government control.

Utilizing their business skills to identify new markets for agricultural and other products, the student team is working with PASO to develop a path away from growing illicit crops to moving toward legal products. Along the way, the team with their partner must address the challenges of governance, security and community trust. Toward these ends, they are building relationships with other organizations heavily involved in the conflict transformation process in Colombia, including the government, the United Nations, private companies and NGOs.

Bringing together diverse organizations around a common goal — coca eradication — can exponentially shift the program’s trajectory in a way that cannot be achieved by business alone. The students learn that collaboration across groups, although certainly not the most efficient process, is nonetheless the only way to address such intractable problems as coca cultivation.

Fourth and finally, the learning process does not stop when the students get on the plane to fly home. Personal reflection is a critical component of the learning process. Each student must come to terms with and develop their own understanding of their experiences in the field. The classes in the second half of the semester support this reevaluation process as we return to core issues of development, corruption and the role of businesses in society. As students now have new perspectives from their time in the field, they must reassess what they believe on such critical issues. This critical importance of reevaluation when confronted with new information becomes a lesson the students take with them through life.

Of note is how inspiring these opportunities are to Business on the Frontlines alumni, now advanced in their professional careers. These alumni certainly have the means to travel around the world for vacation if that is what they wish to do. Instead, 23 alumni returned this year to coach 11 student teams. Over the course of six months, these advisers have dedicated about 400 hours to their partners and teams, including using their personal time to spend two weeks in the field. Alumni are motivated both by the opportunity to serve and to support this student journey of transformation, especially with regard to imagining and creating common ground in order to develop the most impactful solutions for partners to make a difference in the lives of those they serve.

Of note is how inspiring these opportunities are to Business on the Frontlines alumni, now advanced in their professional careers. These alumni certainly have the means to travel around the world for vacation if that is what they wish to do. Instead, 23 alumni returned this year to coach 11 student teams. Over the course of six months, these advisers have dedicated about 400 hours to their partners and teams, including using their personal time to spend two weeks in the field. Alumni are motivated both by the opportunity to serve and to support this student journey of transformation, especially with regard to imagining and creating common ground in order to develop the most impactful solutions for partners to make a difference in the lives of those they serve.

LESSONS FOR US ALL

Today, it sometimes seems that members of our society live in an echo chamber, hearing only thoughts that they agree with, talking to people who agree with them, reading what supports their point of view. So what? What can Business on the Frontlines teach all of us in dealing with conflict in our lives?

First and foremost, we must acknowledge at a very fundamental level that our society’s most pressing problems cannot be solved only by business or government or charities or even just by those who agree with us. The solution to difficult problems lies in the common ground we imagine and then create together.

First and foremost, we must acknowledge at a very fundamental level that our society’s most pressing problems cannot be solved only by business or government or charities or even just by those who agree with us. The solution to difficult problems lies in the common ground we imagine and then create together.

Second, we must recognize the value of dialogue in society. We must be willing to engage in conversation with those whose perspectives, life experiences, opinions are different from our own. From those discussions, sprout the early ideas that, after much work, become potential solutions.

Third, through the process of reflection, we must be willing to reevaluate honestly and comprehensively our own perspectives as we gain new information. Future progress depends on such ongoing reassessments of what we actually think.

The Business on the Frontlines program prepares and then takes students through this journey of discovery. The students gain a visceral sense that the imagination and creation of common ground is both possible and worthy of the effort. They take this lesson into their professional careers and personal lives as they continue to live out Father Sorin’s mission for the University of Notre Dame to be a powerful force for good in the world.

To learn more about Business on the Frontlines, visit botfl.nd.edu.

VIVA BARTKUS

VIVA BARTKUS

Dr. Viva Ona Bartkus, associate professor of management, co-founded the Notre Dame MBA course Business on the Frontlines a dozen years ago with a vision for teaching business students how to find solutions to some of the most intransigent problems plaguing societies in post-conflict countries.

Comments