'HOUSING IS HEALTH'

By | Spring 2020

DR. PAUL GREGERSON WAS SCARED THE FIRST TIME HE VISITED SKID ROW. NOW, HE’S ONE OF THE NATION’S LEADERS IN UNDERSTANDING THE HEALTH CARE CHALLENGES OF THE HOMELESS.

Dr. Paul Gregerson fell into working with the homeless population of Los Angeles partly by happenstance and partly because of what he called a “spiritual transformation” that occurred while he earned an Executive MBA at Notre Dame.

After 10 years as an emergency room internist in the L.A. County hospital, Gregerson wanted to pursue his interest in business administration. His father’s health was faltering, and the time on campus — at the Grotto and Basilica — helped Gregerson reflect on his family, career and future.

A friend asked him to help out some weekends at a homeless health clinic when he was back in Los Angeles, between monthly trips to South Bend. The scene was a shock to his worldview.

A friend asked him to help out some weekends at a homeless health clinic when he was back in Los Angeles, between monthly trips to South Bend. The scene was a shock to his worldview.

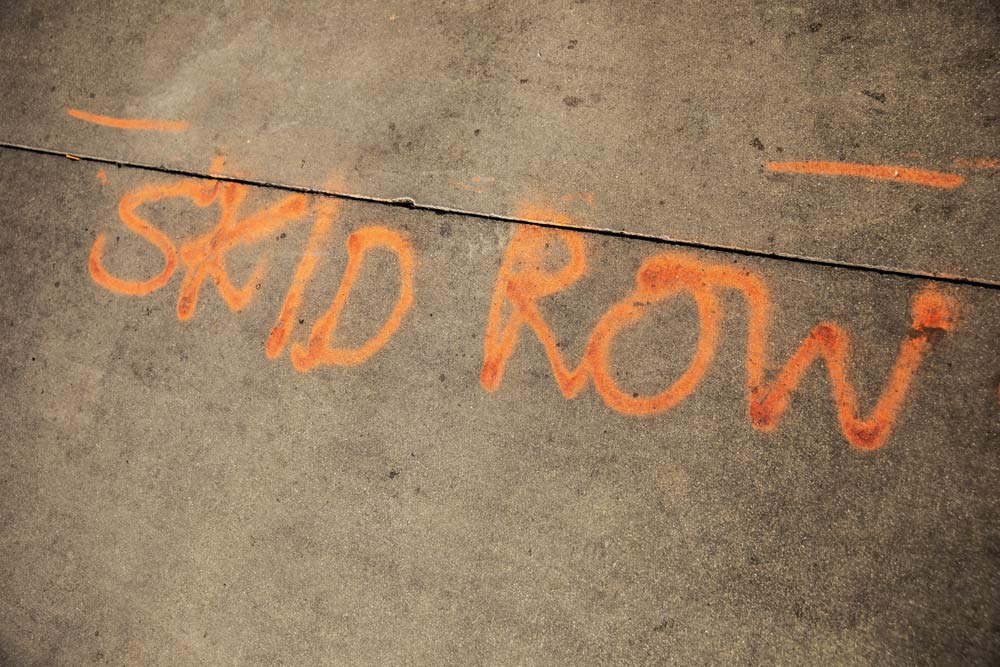

“There’s no place in the world like Skid Row,” he said. “Several thousand people in tents, just blocks and blocks of it. When I first drove down there, this was something I’d never been exposed to. I actually was scared the first time. It was the furthest thing from my mind that I’d end up doing this.”

Yet he began working more often at the clinic and less in the emergency room. The Mendoza EMBA program challenged his weaknesses in technology and public speaking and taught him new ways to work in groups with others. He also got to spend time with his father, who lived nearby.

“I left the program a different person,” he said. “And with my father, I knew he had a real finite time, that we all have finite time. I realized I could help a vulnerable population.”

“I felt so fulfilled working with them. I just fell in love with the patient population.”

DRAWN TO CARE

Gregerson grew up on the south side of Chicago with two brothers and two sisters. His mother was a junior high school teacher and his father an attorney with “a real concern for social justice.”

“There was one thing I was very sure of, that I wanted to be a doctor,” he said by phone in mid-March, just as the coronavirus began to put the country on lockdown. “I’m not even quite sure how that started or where it originated from, but it’s definitely something that was present right from the start.”

He went to college at Marquette University and medical school at the associated Medical College of Wisconsin. Never a fan of Chicago weather, he visited some med school friends in the City of Angels over Christmas break. It was 75 degrees and sunny. They went to the Rose Bowl game. “There was only one place I wanted to live after that,” he said.

In 1985, he started a residency at Los Angeles County–USC Medical Center, and during that time he also started working in the county hospital’s emergency room. He stayed for a decade after residency before deciding to explore other options.

His father’s health was the final straw, with the trips to campus an opportunity to visit him. His earlier education came before cell phones or the internet. He had an AOL connection but rarely used it, as well as little experience in business analytics or accounting. These deficiencies were rapidly addressed.

“Notre Dame is such an experience of family,” he said. “It was a time in life to reflect — really appreciating the opportunity to learn. The way the program was structured, with group projects, the whole experience was so amazing.”

He received his executive MBA in 2001 and returned to L.A., where his growing interest in homeless health care collided with fortuitous circumstance. The clinic where he worked weekends was the John Wesley Community Health Institute (JWCH) that served Skid Row. The position of chief medical director there would open up at the right time.

BUILDING A SYSTEM

JWCH began 60 years ago when a group of L.A. County Hospital doctors created a private, nonprofit public benefit corporation dealing with health services and medical research. In 1995, Los Angeles health services restructured its approach to indigent care in an attempt to reduce its dependence on federally funded emergency room care. JWCH took over the county homeless clinic in Skid Row with a goal of building an integrated system of preventative and primary care.

The clinic did little more than urgent care when Gregerson arrived five years later. He said homeless are people like everyone else — who read newspapers and watch March Madness — but who had “suffered so much trauma.”

The clinic did little more than urgent care when Gregerson arrived five years later. He said homeless are people like everyone else — who read newspapers and watch March Madness — but who had “suffered so much trauma.”

“These people have been spurned and abused,” he said. “There’s no sense of social support. What amazed me, they were so thankful for whatever health care they were getting.”

Gregerson was promoted to chief medical director in 2003. With his new MBA, he said he quickly realized “it was where I needed to be.”

The city pulled together about two dozen agencies with some connection to the homeless issue, ranging from social workers and nonprofits to the hospitals and housing department. Gregerson chaired the clinical aspect of an integrated plan that took several years to develop, one that would be the largest in the country.

His clinic had four exam rooms at the time. Now there are 20. Plus, JWCH has expanded to a total of 17 clinics across Los Angeles, including many that serve primarily the Latino population. Besides running the business elements of this expansion, Gregerson is responsible for hiring the doctors.

“I look for people that really want to work with this population, who are not going to accommodate a clock,” he said. “You don’t clock in at 9 and leave at 5. It’s something that’s a part of you, a defined way of living. In medicine, people are sick outside the time you are there. It’s more than a job; it’s very rewarding.”

“I look for people that really want to work with this population, who are not going to accommodate a clock,” he said. “You don’t clock in at 9 and leave at 5. It’s something that’s a part of you, a defined way of living. In medicine, people are sick outside the time you are there. It’s more than a job; it’s very rewarding.”

Michael Cousineau, a professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, authored a 2003 report, “Neglect on the Streets,” that launched the Skid Row Homeless Health Initiative. He has worked with Gregerson since then to implement change.

“There are only a handful of doctors in the United States whose life mission is providing health care to people experiencing homelessness,” Cousineau wrote in an email. “Paul Gregerson is one.

“He is now one of the nation’s leaders in understanding the health care challenges that homeless people face, and importantly, promoting models of care for people on the streets and in shelters,” he added.

More than 150,000 people in California were homeless between 2018 and 2019, an increase of 16%. The state has the fastest growing homeless population of any of the states. The total number of homeless in the U.S. on any given night is estimated to be greater than 568,000, according to the 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress.

CLINICAL CONNECTIONS

While primarily an administrator, Gregerson makes time for the practice that drew him into homeless health in the first place. He sees patients twice a week, and he uses that time to engage another passion by teaching USC medical students.

“I would never give up the clinical side of medicine,” he said. “I’ve always loved interaction with patients. There’s nothing like helping another human being who’s sick and needs help. Doctors see people at their most vulnerable. That’s an honor and a trust.”

“I would never give up the clinical side of medicine,” he said. “I’ve always loved interaction with patients. There’s nothing like helping another human being who’s sick and needs help. Doctors see people at their most vulnerable. That’s an honor and a trust.”

Homeless patient cases are complex. They suffer from chronic problems like emphysema and diabetes, which are compounded by mental health and drug problems. They often are not compliant with doctor’s orders. Because of this, he watches his staff closely for burnout. “It can be wearing because if you’re caring and have compassion, it’s hard to see them get arrested, relapse or have a psychotic break,” he said.

There are nearly 60,000 homeless people in Los Angeles County, with about 75% of them living unsheltered — either in tents or cars or just on the sidewalks. “Even if you have the medical resources to do everything else, the bottom line is these people are still leaving the clinic and going back outside to a place that’s dangerous and unhelpful,” he said.

He recalled two patients who stick out in his memory for different reasons. One was a young man in his late 20s who grew up in South Central, a predominantly Latino area near downtown. He was schizophrenic and depressed. He told Gregerson about his past, a tragic tale of neglect and physical and sexual abuse. He drifted into gang life and even admitted to taking people’s lives. Tears were shed on both sides.

“I wonder if he will ever recover,” Gregerson said. “By the time we finished, he was able to smile and hug. I still check his medical records. Cases like that happen all the time. It’s an example of an experience I’ll never forget.”

A more positive story was a woman who had been on the streets for 25 years. She was a drug user and prostitute, so thin she looked like she had cancer. The clinic put her in a program for people likely to die without intervention. She went on a methadone program and her health started to rebound after about nine months.

“She’s stopped using and prostituting,” Gregerson said. “Two years later, she’s still mentally ill, but she’s a different person. She’s leading groups. She went into permanent housing and she’s now living independently.”

ESPECIALLY VULNERABLE

Gregerson said the homeless population is especially susceptible to pandemic outbreaks like coronavirus. The Skid Row population is older, with many in the 40-60 age range, most of whom have been living on the streets for years. He said his patients are at least twice as vulnerable.

“The coronavirus is very dangerous to this population,” he said. “It’s more of a danger to those who are older and weaker, and living outside ages you. Emphysema is very common. The problem is, they are living very close to each other. They don’t have access to sanitary conditions where you can wash your hands. The only risk that we don’t have is travel.”

“The coronavirus is very dangerous to this population,” he said. “It’s more of a danger to those who are older and weaker, and living outside ages you. Emphysema is very common. The problem is, they are living very close to each other. They don’t have access to sanitary conditions where you can wash your hands. The only risk that we don’t have is travel.”

Gregerson estimates only about 10% of the Skid Row homeless had any health insurance when JWCH started. In recent years, he said that number grew to nearly 80% insured with access through the Affordable Care Act. Regardless, those patients need health care, he said.

“The corona outbreak is a good example,” he said. “How could you ever deny people health care? A human being is a human being. Same with living in the streets. Why should anyone live like this in the richest country in the world?”

Years of experience on Skid Row have taught Gregerson the harsh reality of its inhabitants’ lives. There are victories and setbacks, but his goal is to “meet them where they are” and provide care without judgment. The damage can be too great to heal, but improvement is possible.

“We know most of these people are never going to work again,” he said. “The goal is to improve their quality of life. Help them to live independently and make them want to get up every day.”

The current policy debate over how to help the homeless focuses on when to provide housing. Traditional programs have required the homeless to undergo drug and alcohol addiction treatment before moving them into transitional housing. The idea was that they have to be sober and straight to take responsibility for maintaining a residence.

But a recent national movement for “housing first” prioritizes providing the homeless with housing regardless of their sobriety. The theory is that improved health and sobriety are not possible without the stable base of a home first. The program has had some success in L.A. and other parts of the country.

Gregerson said getting people off the streets is the first step, whether through rapid housing for those with temporary loss or through transitional housing with full health and social services for those who have been on the streets for years. Health and housing are interconnected.

“The bottom line is that health care is a human right and so is housing,” he said. “I’d most like to see permanent supportive housing and temporary housing for a start. We can talk about the medical component. I always want more doctors and better equipment, but housing is health for these people.”

Photos by John Davis Photography

JWCH Institute Inc. is a private nonprofit health agency whose mission is to improve the health status and wellbeing of under-served segments of the population of the Los Angeles area through the direct provision or coordination of health care, health education, services and research.

jwchinstitute.org

Comments